George Alogoskoufis

A shorter version of this article was published in Greek in the newspaper TA NEA on November 15, 2025

________________________________________________________

Productivity is the fundamental determinant of long-term economic growth and national prosperity. An economy’s ability to produce more value with the same or fewer resources reflects not only its technological progress but also the overall effectiveness of its institutions, firms, and human capital. For the Greek economy, increasing productivity is the central challenge of the post-crisis era, as it is directly linked to sustainable growth, improved living standards, and enhanced competitiveness.

Which conditions are required to strengthen labor productivity, total factor productivity (TFP), and technological progress in the Greek economy? This article focuses both on the theoretical mechanisms connecting these factors to economic growth and on the policy and institutional reforms needed to promote them.

Theoretical Framework

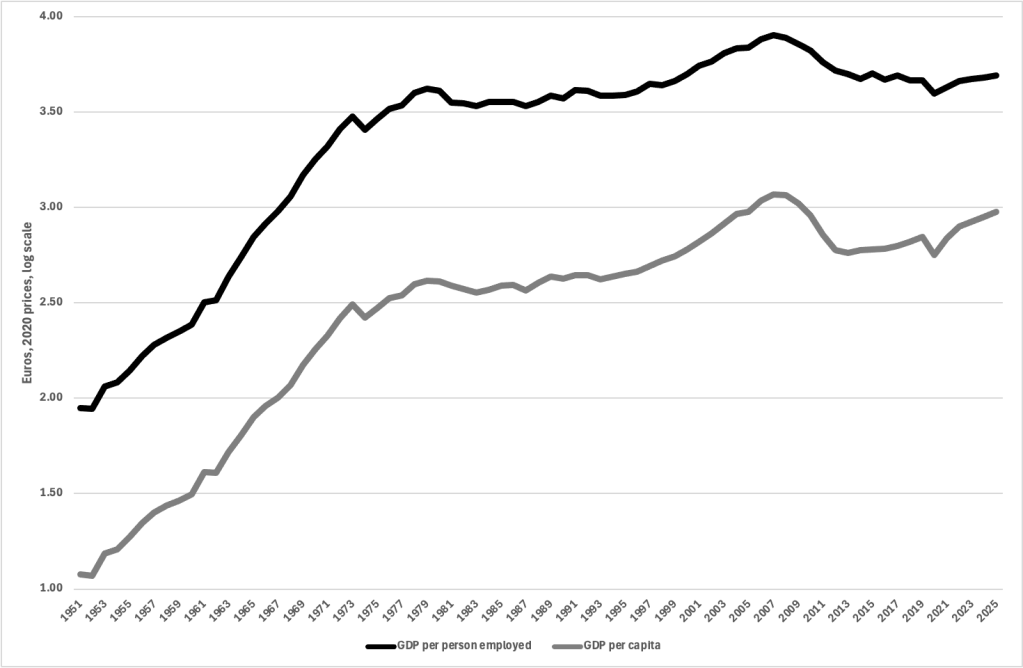

Labor productivity measures output per worker or per hour worked and depends on physical capital, human capital, and technological progress. The close correlation between labor productivity and Greece’s real GDP per capita since the early 1950s is clearly visible in the graph that follows.

The period of strong growth during the 1950s and 1960s was driven by the rapid rise in labor productivity, itself the result of high investment in both human and physical capital.

From the mid-1970s onwards, there was a noticeable slowdown, while during the 1980s labor productivity growth was almost zero, as was the growth of real GDP per capita. Growth gradually began to recover during the 1990s and accelerated temporarily following Greece’s entry into the euro area. After the global recession of 2008–2009 and the sovereign debt crisis of 2010, both labor productivity and real GDP per capita collapsed.

The gradual recovery of real GDP per capita after 2014 was not accompanied by a corresponding increase in labor productivity; instead, it is largely attributable to the decline in the population rather than to improvements in productivity.

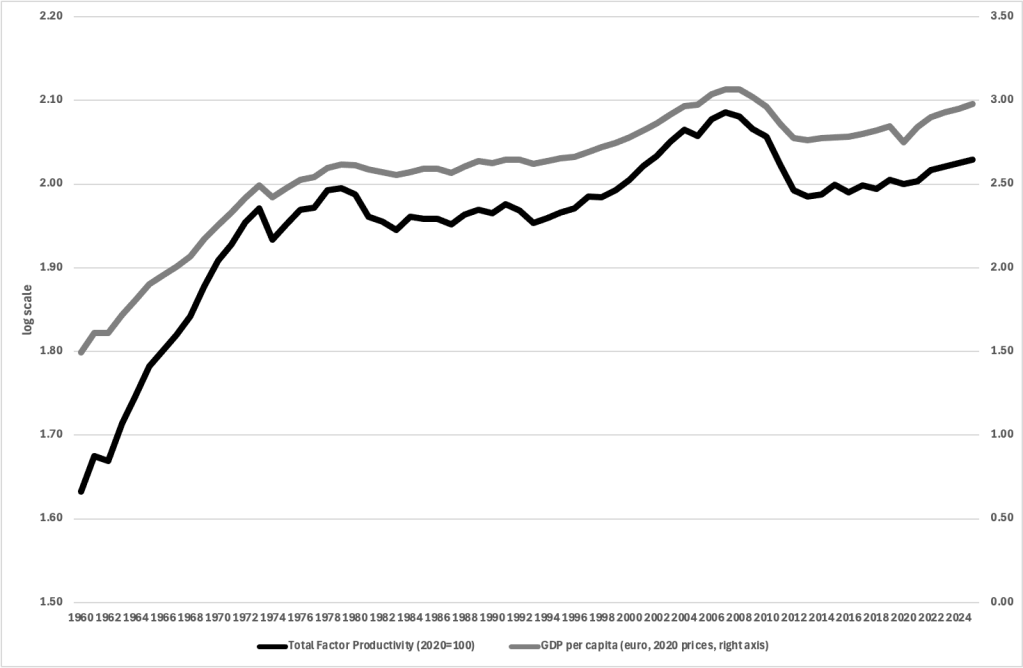

In contrast, total factor productivity (TFP) captures the efficiency with which labor and capital are combined, regardless of the quantity of inputs. The evolution of total factor productivity in Greece, as calculated by the services of the European Commission, is shown in the graph that follows.

The trajectory of total factor productivity is also closely correlated with the evolution of real GDP per capita as well as with that of labor productivity. Despite its increase after 2014, total factor productivity in Greece remains significantly below the levels observed in the years before the 2010 crisis.

According to the neoclassical growth model of Solow (1956), technological progress is the primary long-run driver of increases in income per capita. In more recent endogenous growth models (Romer, Lucas, Aghion & Howitt), productivity is linked to innovation, research and development (R&D), knowledge accumulation, and the effectiveness of institutions.

The Greek economy, despite the substantial rise in per capita GDP after 1995 and entry into the Eurozone, exhibited low TFP growth compared with other European economies. The crisis of the 2010s revealed deep structural bottlenecks that had constrained sustainable growth.

Determinants of Labor Productivity Growth

1. Human capital

Improving skills, education, and training is essential for raising productivity. Greece has a high share of university graduates but lags behind in technical and digital skills and in linking education with labor-market needs.

This requires:

- modernization of curricula,

- strengthening vocational education,

- lifelong learning and closer university–industry collaboration.

Leveraging the human capital lost during the crisis years (brain drain) is also crucial for long-term development.

2. Capital equipment and investment

Increasing investment in technological and productive equipment enhances productivity through economies of scale and adoption of new technologies.

EU Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) resources can help renew the productive capital stock and support digital and green investments. However, as these funds are temporary, more is required to boost domestic savings in order to finance higher investment without recourse to foreign borrowing.

3. Production organization and business practices

Productivity is strongly affected by internal firm organization. Greece is characterized by fragmented small and medium-sized enterprises, limited professional management, and insufficient use of technology.

Policies must encourage:

- mergers and collaborations among SMEs,

- improved management practices,

- stronger corporate governance.

Increasing Total Factor Productivity (TFP)

TFP reflects institutional, organizational, and technological improvements. Low TFP in Greece stems from weak institutions, bureaucracy, tax instability, and limited competition.

1. Institutional environment

The effectiveness of the state and the quality of institutions determine the investment climate. Essential reforms include:

- digitalization of public administration,

- faster judicial processes,

- a stable tax framework,

- reducing bureaucracy and corruption.

Such reforms increase efficiency and lower transaction costs.

2. Competition and market functioning

Liberalizing markets and removing regulatory barriers increases firm efficiency. Competition promotes innovation and technology diffusion.

Greece must advance:

- liberalization of closed professions,

- improved competition in product and service markets,

- more efficient energy and logistics sectors.

3. Innovation and university–industry collaboration

Low investment in R&D (around 1.5% of GDP) restricts knowledge creation. Strengthening ties between universities and productive sectors—through spin-offs, clusters, and incubators—is essential for raising TFP.

Technological Progress as a Long-Term Growth Engine

Technological progress expresses an economy’s ability to adopt, adapt, and generate new technologies. For Greece, technological progress must be endogenous, arising from internal innovation rather than solely from imported technology.

1. Research and Development (R&D)

Raising public and private R&D spending is necessary. Policies should include tax incentives for innovative firms, grants for start-ups, and support for technological entrepreneurship.

2. Digital transformation

Integrating digital technologies (AI, big data, cloud, 5G) into business operations and public administration improves efficiency and reduces costs. Greece’s digital strategy must be linked to education and accessible digital infrastructure for SMEs.

3. Openness and international integration

Participation in global value chains facilitates technology transfer. Foreign direct investment (FDI) can act as a channel for technological spillovers, provided local linkages and institutional stability are in place.

4. Reversing the brain drain

Bringing back skilled professionals from abroad can boost technological capacity. Programs like ReBrain Greece are a first step but require stronger incentives for employment and innovation.

Institutional and Policy Priorities for Greece

Increasing productivity requires a comprehensive national strategy that combines microeconomic and macroeconomic policies.

| Pillar | Key Policies |

| Human capital | Modernized education, STEM, lifelong learning |

| Physical capital | Investment incentives, RRF absorption |

| Institutions | Digital state, stable tax system, faster justice |

| Innovation | R&D support, clusters, public–private partnerships |

| Markets | Market liberalization, competition, reduced regulation |

| Openness | Export promotion, international partnerships, FDI |

Consistency, political stability, and trust in institutions are essential for the success of these reforms.

Conclusions

Labor productivity, total factor productivity, and technological progress are the key pillars of long-term economic growth in Greece. Strengthening them requires:

- investment in human and physical capital,

- institutional and business environment reforms,

- policies promoting innovation and technological upgrading,

- and above all, a stable and predictable environment that fosters trust.

Only through continuous productivity improvement can Greece achieve sustainable growth, higher real wages, and stronger international competitiveness. Transitioning to a new growth model based on knowledge, innovation, and efficiency is the central development challenge for the coming decades.

Link to the shorter article in Greek in the newspaper ΤΑ ΝΕΑ