This article is adapted from an article in Greek, published in the newspaper To Vima, on December 29, 2024

____________________________________________

Over the past five years, the global economy has faced successive crises due to the pandemic and a series of other disruptions such as the war in Ukraine, the crisis in the Middle East, the resurgence of inflation, the adoption of restrictive monetary policies, and the effects of climate change.

For 2025, the international political and economic environment is characterized by increased uncertainty due to government changes in the US, Britain and elsewhere, the weakening of governments in France and India, and electoral uncertainty in view of political developments in Germany. In addition, a trade war looms if the US increases tariffs on China and its trading partners as expected, the free movement of people in the Schengen area faces problems, while developments in the adoption of green energy and artificial intelligence applications will continue to change both the energy and technological environment.

In this fluid landscape, the global economy appears to be maintaining its growth momentum, while the European economy is expected to experience a gradual recovery from the stagnation of recent years. The fight against inflation appears to have been relatively successful, and central banks are expected to continue the reduction in interest rates that began in 2024.

Global Economic Outlook

According to the latest estimates of the International Monetary Fund, global growth is expected to remain steady but subdued.

Compared to forecasts six months ago, the growth outlook for the United States has improved, but this is offset by a downgrade in the outlook for other advanced economies, particularly the largest European countries. Similarly, in emerging markets and developing economies, disruptions in the production and transport of commodities – particularly oil – conflicts, political unrest and extreme weather events have led to downward revisions to the outlook for the Middle East and Central Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. These were offset by upgrades to forecasts for emerging Asia, where rising demand for semiconductors and electronics, driven by significant investment in artificial intelligence, boosted growth, a trend supported by significant public investment in China and India. Five years from now, global growth should reach 3.1 percent – a modest performance compared with the pre-pandemic average.

As global disinflation continues, services price inflation remains elevated in many regions, requiring caution in adjusting monetary policy to ensure a smooth landing.

European and Greek Economic Outlook

After a prolonged period of stagnation, the EU economy is returning to moderate growth rates, while the disinflation process continues.

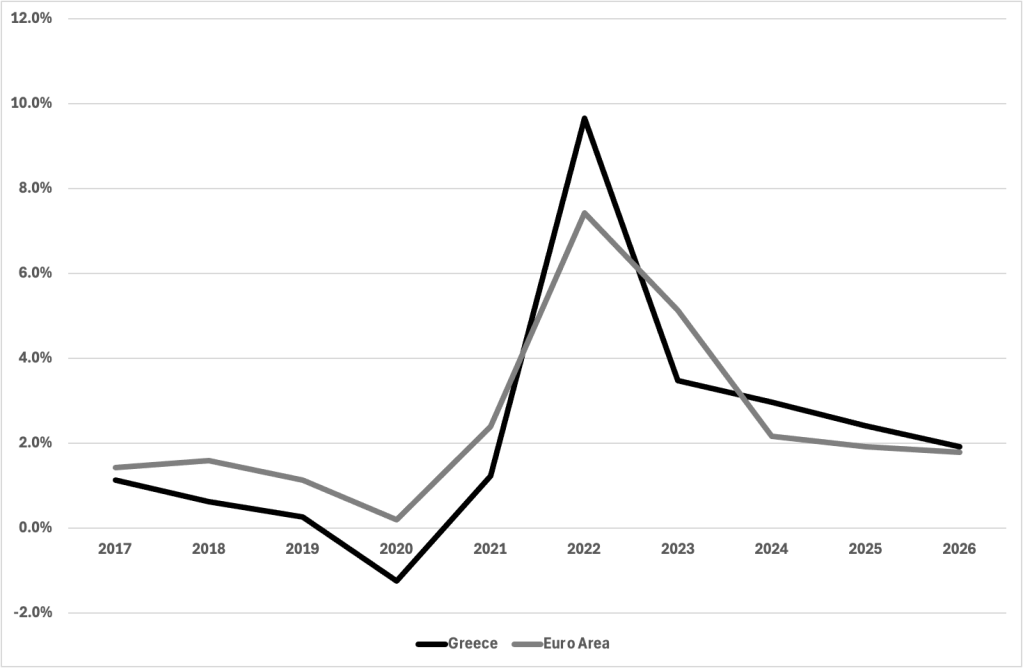

The European Commission’s autumn forecast projects GDP growth in 2024 of 0.9% in the EU and 0.8% in the euro area. Economic activity is projected to accelerate to 1.5% in the EU and 1.3% in the euro area in 2025 and to 1.8% in the EU and 1.6% in the euro area in 2026.

Inflation in the euro area is expected to more than halve in 2024, to 2.4%, from 5.4% in 2023, before gradually easing to 2.1% in 2025 and 1.9% in 2026. The disinflation process for the EU as a whole is projected to accelerate even more in 2024, with inflation falling to 2.6% from 6.4% in 2023 and continuing to decline to 2.4% in 2025 and 2.0% in 2026.

Service price pressures remain high, but are projected to moderate from early 2025, driven by a slowdown in wage growth and the expected recovery in productivity, and supported by negative base effects. This sets the stage for inflation to fall towards the 2% target by the end of 2025 in the euro area and 2026 in the EU as a whole.

The EU labour market held up well in the first half of 2024 and is expected to remain strong. Employment growth in the EU is expected to continue, albeit at a slower pace, from 0.8% in 2024 (0.9% in the euro area) to 0.5% in 2026 (0.6% in the euro area).

In October, the unemployment rate in the EU reached a new historical low of 5.9%. In 2024 as a whole, it is forecast to rise to 6.1% (6.5% in the euro area) and decline further thereafter, reaching 5.9% in 2025 and 2026 (6.3% in the euro area).

Regarding Greece, economic activity is expected to expand by 2.1% in 2024 and to maintain a broadly similar growth in 2025 and 2026, supported by the implementation of the Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP). Unemployment, already below 10%, is expected to continue to decline but more slowly than in the past. Inflation is forecast at 3.0% in 2024 and is expected to moderate only gradually to around 2.0% by 2026.

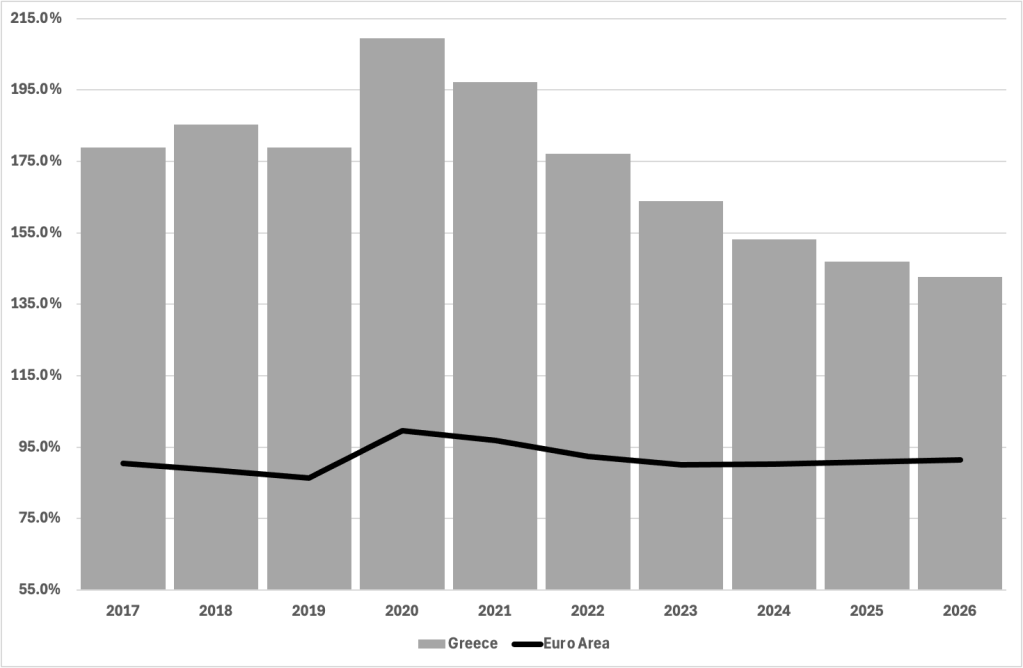

As many Member States work to reduce their debt to GDP ratios, the EU general government deficit is expected to decline in 2024 by around 0.4 percentage points, to 3.1% of GDP and to 3.0% in 2025. In 2026, positive economic momentum is projected to further reduce the deficit to 2.9%. In the euro area, the deficit to GDP ratio is projected to decline from 3.0% in 2024 to 2.9% in 2025 and 2.8% in 2026.

However, the EU’s government debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to increase, from 82.1% in 2023 to 83.4% in 2026. This follows a decline of almost 10 percentage points between 2020 and 2023 and reflects the impact of still high primary deficits and rising interest expenditure, which are no longer offset by high nominal GDP growth as inflation declines. In the euro area, government debt is projected to increase from 88.9% of GDP in 2023 to 90% in 2026.

Regarding Greece, the general government deficit is projected to continue to decline due to moderate expenditure growth. Together with the steady growth of nominal GDP, this contributes to a steady reduction of the public debt-to-GDP ratio to close to 140% of GDP by 2026.

Medium-Term Growth Prospects and the Need for Reforms

The main problem of both the global, European and Greek economies is the sluggishness of medium-term growth prospects. In order to strengthen growth prospects, deep structural reforms are necessary, while support for the most vulnerable social groups should be maintained.

The reforms required are described both in the recent Draghi report on the European economy and in the older Pissarides report on the Greek economy. They are also analyzed in my recent book, Before and After the Political Transition of 1974 (Gutenberg Publications, 2024, in Greek) and my recent working paper on Greece published by the Hellenic Observatory of the London School of Economics (GreeSE Paper no 198, Hellenic Observatory, London School of Economics).

The need for reforms in the Greek case is highlighted by the evolution of a series of indicators.

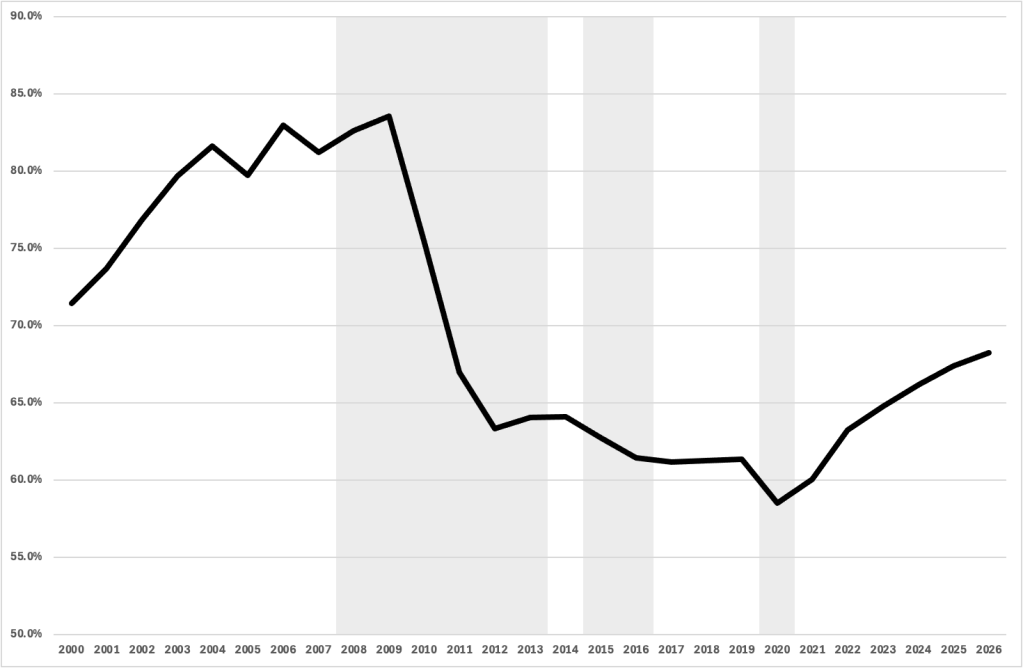

The most important of these is the negative evolution of per capita income as a percentage of the EU-15. From over 80% of the corresponding EU-15, Greek per capita income fell to 60% after the Greek financial crisis of 2010. Since 2021 it begins to show a small increase but this increase is slow and in no case does Greece’s relative per capita income seem to approach the levels of the period before the great slump of the Greek economy in the period 2010-2013.

For Greece, the high current account deficit is also a worrying development, an indicator of the weaknesses of the Greek economy’s production model, low structural competitiveness and the inadequacy of national savings in relation to investment. While in the euro area the current account is in surplus, in Greece it is expected to continue to be in significant deficit, with a deficit exceeding 5% of GDP.

Another worrying indicator is the continued low level of fixed capital investment relative to GDP. While before the 2010 crisis, fixed capital investment exceeded 20% of GDP, during the crisis it fell to 10% of GDP. After 2019, there has been a recovery in investment, but it remains below 20% of GDP. Furthermore, the increase in investment that has occurred is largely due to investment in housing and not to investment in new, outward-looking productive sectors. Combined with low private savings, low fixed capital investment constitutes a critical imbalance for the Greek economy and contributes to its disappointing growth performance.

Finally, despite its reduction in recent years, public debt remains particularly high relative to GDP, and significantly higher than in the period before the 2010 crisis or than the corresponding percentage in the other euro area countries. This indicates the need for continued and intensified fiscal adjustment efforts.

Reforms to address the macroeconomic imbalances and structural weaknesses of the Greek economy entail short-term political costs, due to the fact that their implementation entails losses for some social groups.

Even if those affected by individual reforms are in a minority, these losses cause political costs for the governments that will undertake them. On the other hand, the benefits of reforms do not usually appear immediately, but over time. Consequently, governments, both in the EU and in Greece, generally avoid difficult but beneficial reforms, the political cost of which they would bear during their term of office, while the benefit would most likely appear during the term of office of their successors. Thus, due to the inability of the political system to promote political consensus, each government chooses the path of a minor reform effort, with extremely unpleasant results for the European and Greek economy.

It is imperative that there is a minimum political consensus regarding the direction and scope of the required structural reforms in the economy and the state, in order to substantially improve the anemic growth prospects in both the EU and Greece.

In the case of Greece, the 2025 budget is generally in the right direction, particularly with regard to fiscal consolidation and social protection, but the reforms that have to be implemented in order to address the structural weaknesses of the Greek economy and accelerate the rates of economic growth are many and by no means negligible.

Link to GreeSE Paper no 198, Hellenic Observatory London School of Economics