George Alogoskoufis

This article is adapted from an article in Greek, published in the special supplement of the newspaper To Vima, December 31, 2023. It has been updated on April 25, 2024, following the latest revision of the IMF’s medium-term projections.

___________________________________________________________

The most important legacy of 2023 for Greece is the change in the political landscape that has occurred as a result of the national elections. For the first time since the restoration of democracy in 1974, a government enters its second term strengthened both electorally and politically. In addition, it faces an official opposition with a deep legitimacy crisis which is no longer considered a credible alternative for governing the country.

The election result offers a historic opportunity for the government and the country. Although nature abhors a vacuum, and sooner or later an alternative and more credible opposition will emerge, a government with free hands, such as the current one, has no reason to delay moving forward with boldness and determination in promoting the difficult but beneficial reforms needed for the economy and the country.

After all, the predicted medium-term economic developments do not justify complacency.

The rapid recovery of the Greek economy from the deep recession of 2020 caused by the pandemic was a positive development. However, for the next few years all international organizations expect a significant slowdown in the rate of economic growth.

According to the IMF’s latest April 2024 forecasts, for the six-year period 2024-2029, the projected average annual GDP growth rate is only 1.6%. Even in 2029, Greece’s real GDP is forecast to be just €213.9 billion in 2015 prices, down from €239.7 billion in 2007, before the international financial crisis and the debt crisis of 2010. Twenty plus years after the twin crises, Greece’s real GDP is projected to remain 11% below the pre-crisis level. The same applies for real GDP per capita, which in 2028 is projected to be 5.0% lower than its peak in 2007 (see Graph 1).

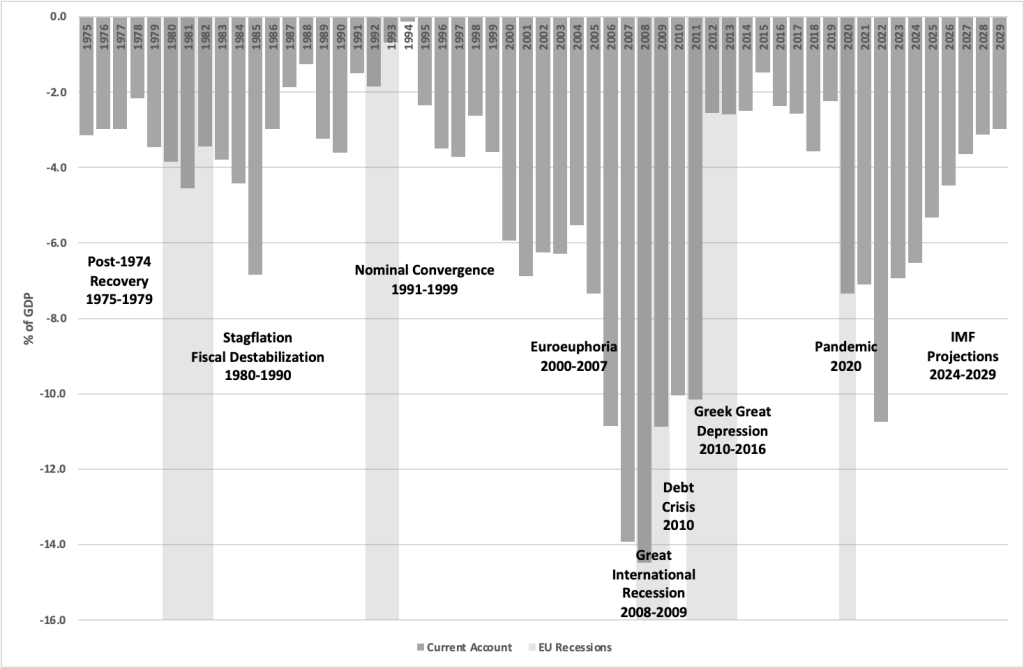

The significant widening of the current account deficit during the pandemic and its further widening since the Greek economy began to recover from the deep recession of 2020 is the clearest indication of the structural weaknesses that continue to plague the Greek economy. The current account deficit in the four years after the pandemic (2000-2023) rose to an average of 8% of GDP relative to only 2.7% of GDP in the previous four years (2016-2019). It is forecast to decline to 6.5% of GDP in 2024 and continue to decline thereafter. However, it is projected to remain above 3% of GDP until 2028 (see Graph 2). This is a very worrisome development, as the main cause of the 2010 credit crisis and the Great Depression that followed was the rapid accumulation of external debt through persistent current account deficits.

For Greece, after the restructuring of its debt in 2012, the immediate risks from a possible new international financial crisis are limited. Until 2032, the external public debt of Greece will bear relatively low interest rates, due to the restructuring of 2012. It is mainly because of this that the transition to investment grade for Greek bonds took place. However, few of the structural weaknesses of the Greek economy have been addressed and the de-escalation of public debt as a percentage of GDP is far from satisfactory, as the public deb to GDP ratio remains significantly above its 2010 level (see Graph 3).

In the medium term, the problem of strengthening the economic recovery by improving the international competitiveness of the Greek economy, as well as the problem of the more rapid de-escalation of the ratio of public debt to GDP, constitute the two biggest challenges of economic policy.

The main focus of the government’s economic policy must be to reduce unemployment more quickly, increase labor force participation, especially of young people and women, reverse the migration of skilled young Greeks and to adopt structural reforms that will lead to a significant increase in investment, productivity and research and development. At the same time, an attempt must be made to gradually reverse the adverse demographic trends.

More important are the structural reforms that will lead to increased investment, productivity and technical progress and boost economic growth. The investment rate in Greece, especially after the 2010 crisis, is at hopelessly low levels. The same applies to the rate of growth of total productivity and technical progress. The government must make full use of the Pissarides report, which proposes several reforms which, if implemented, could usher in a new period of high growth. Corresponding reforms have been proposed in my paper Greece Before and After the Euro: Macroeconomics, Politics and the Quest for Reforms, (Ch. 3, in Alogoskoufis, G. and Featherstone, K. Greece and Euro: From Crisis to Recovery, ebook, Hellenic Observatory, London School of Economics, 2021), but also by other economists.

I believe that the required reforms are very broad and concern at least six areas:

- The non-competitive functioning of markets for goods and services

- The dysfunctional labor market

- The non-competitive financial system

- The inefficient public sector and the bureaucracy

- The tax and welfare system

- The educational system

Despite some efforts by previous governments, the biggest problems in these areas have not been addressed.

But why should the current government push through the difficult reforms that its predecessors have largely avoided over the past 35 years?

Precisely because of the political hegemony it has secured! The reforms required entail short-term costs, due to the fact that their implementation entails losses for some social groups. Even if those affected are minorities, these losses imply political costs for the government that undertakes them. On the other hand, the benefits of reforms usually do not appear immediately but over time. Consequently, the Greek governments of the past fifty years generally avoided these difficult but beneficial reforms, the costs of which would be borne during their tenure, while the benefits would most likely accrue during the tenure of their successors. Thus, due to the inability of the political system to promote political consensus, each government chose to avoid painful reforms, with extremely unpleasant results for the economy and the country.

The current government does not face these restrictions. Due to its political dominance it has a particularly long horizon, as there is no credible alternative successor. It can therefore push through the required reforms with the near certainty that their short-term political cost is not sufficient to destabilize it. In this sense, the occasion is historic. Never before, in the period since the restoration of democracy in 1974, has there been a better opportunity to advance the difficult but beneficial reforms needed for the economy and the country. It is high time for such reforms and the opportunity must not be missed.

Link to the original article in Greek, in the special supplement for 2024 of the newspaper To Vima

Link to Greece and the Euro: Macroeconomics, Politics and the Quest for Reforms

Dear Professor, not only agree with every single word of your article, but I am a strong believer that the Greek society is currently much more mature and ready, than ever before, to accept all these reforms. For me, actually the political message of the national elections was sound and clear, no more populism. The Greek people needs actions that would move the country forward. This resulted to the huge victory of ND and the eradication of the opposition parties.