George Alogoskoufis

This article is based on the remarks of the author, who spoke as a discussant, following the presentation of Chris Pissarides at the Hellenic Observatory public lecture The Economic Challenges for the New Greek Government, October 5, 2023.

___________________________________

The speedy recovery of the Greek economy from the deep recession of 2020 caused by the pandemic has been a positive development. However, for the next few years all international organizations expect a significant slowdown in the rate of economic growth. Given that new clouds have been gathering over the global economy and given the structural weaknesses of both the Euro Area and the Greek economy, the greatest danger is complacency.

For Greece, after the restructuring of its debt in 2012, the immediate risks from a new international financial crisis are limited. Until 2032, Greece’s external public debt will bear relatively low interest rates, due to the restructuring of 2012. For this reason, the transition to investment grade for Greek bonds is confidently expected. However, few of the structural weaknesses of the Greek economy have been addressed, and the de-escalation of public debt as a percentage of GDP is far from satisfactory.

The medium-term prospects of the Greek economy, according to the latest IMF projections of April 2023, leave a lot to be desired.

For the five-year period 2024-2028, the projected average annual GDP growth rate is only 1.4%. Even in 2028, the real GDP of Greece will only stand at 210.8 bn euros of 2015, versus 239.7 bn in the peak of 2007, before the international financial crisis and the great depression following the Greek crisis of 2010. Twenty years after the twin crises, the real GDP of Greece is projected to remain 12% below the pre-crisis level (Chart 1). GDP per capita in 2028 is also projected to be lower than the peak of 2007, by 6.5%.

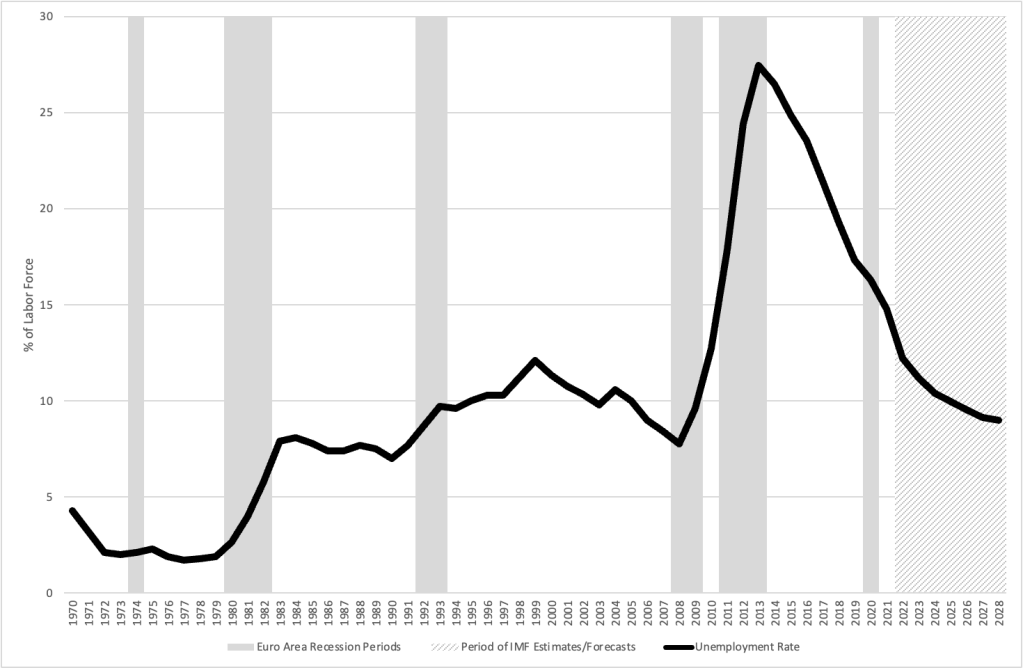

Unemployment is expected to fall from 11.2% of the labor force in 2023 to 9.0% in 2028, thus remaining relatively high. As a reminder, the unemployment rate had fallen to 7.8% of the labor force in 2008, at the beginning of the international financial crisis (Chart 2). It then exploded, especially in the first two years after the sudden stop of 2010.

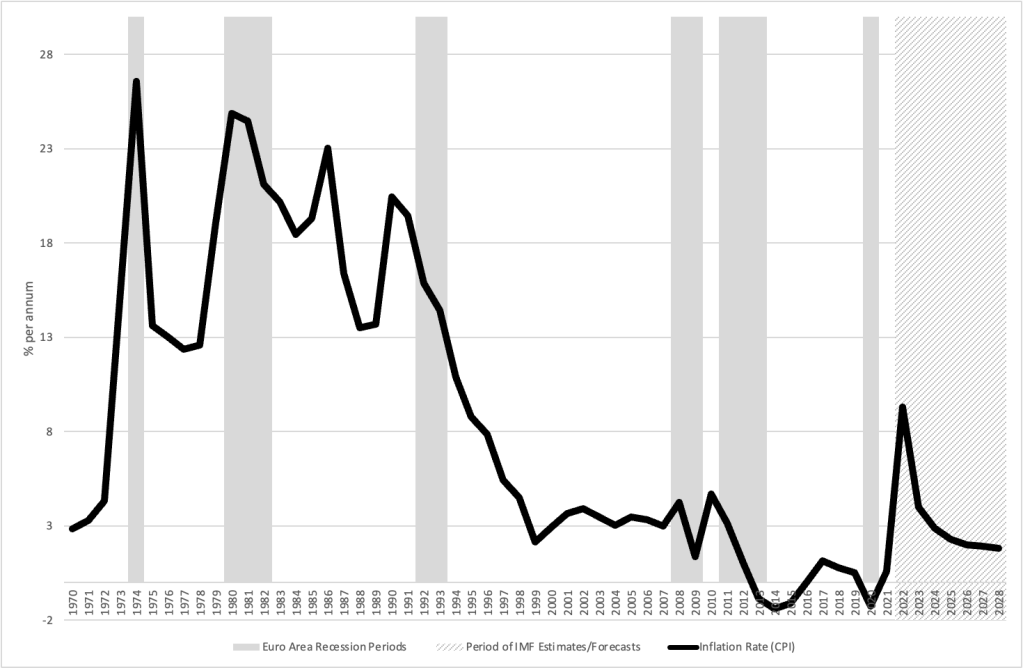

Inflation, which peaked at 9.3% in 2022, is projected fall from around 4,0% in 2023 to 2,9% in 2024 and to settle around 2.0% after 2025, reflecting the anti-inflationary stance of the ECB (Chart 3).

The significant widening of the current account deficit during the pandemic and its further widening just as the Greek economy began to recover from the deep recession of 2020 is a clear indication of the structural weaknesses that continue to plague the Greek economy.

The current account deficit is expected to be at 8.0% of GDP in 2023, down from 9.6% of GDP in 2022. Thereafter it is projected to continue falling, but it is projected to stay above 3% of GDP as far ahead as 2028 (Chart 4). This is a very worrisome development, as the proximate cause of the 2010 sudden stop, and the crisis which followed, was the rapid accumulation of external debt through persistent current account deficits.

Thus, the projections for the rate of GDP growth and the de-escalation of unemployment are rather unimpressive, while those for the current account balance are disappointing. It is therefore imperative that there be an effort for a faster recovery and greater improvement of the international competitiveness of the Greek economy in relation to these projections.

In the medium term, the problem of strengthening the economic recovery by improving the international competitiveness of the Greek economy, as well as the problem of a rapid de-escalation of the ratio of public debt to GDP, constitute the main challenges of economic policy.

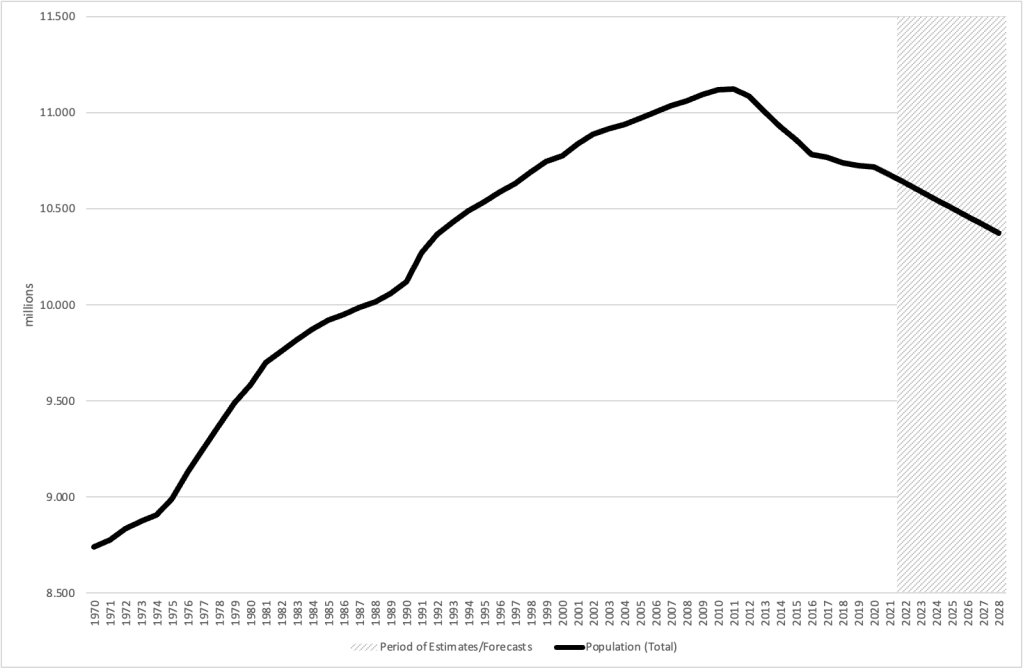

But how will a faster economic recovery and growth be achieved, in a period when the Greek population is actually falling (Chart 5).

The main government focus must be on a faster reduction of unemployment, an increase in labor force participation, especially by young people and women, a reversal of the out-migration of skilled young Greeks and structural reforms that will lead to significant increases in investment, productivity and research and development. At the same time, the gradual reversal of the unfavorable demographic trends must be attempted.

Greece has one of the highest unemployment rates and one of the lowest youth and female labor force participation rates in the euro area. Intensifying unemployment reduction policies and providing strong economic and social incentives to increase labor force participation rates will lead to significant GDP growth even without an increase in average labor productivity. Reversing the brain drain, a trend that was strengthened during the period of the great economic crisis after 2010, will have even better results as these skilled young Greek immigrants are much more productive than the average Greek worker.

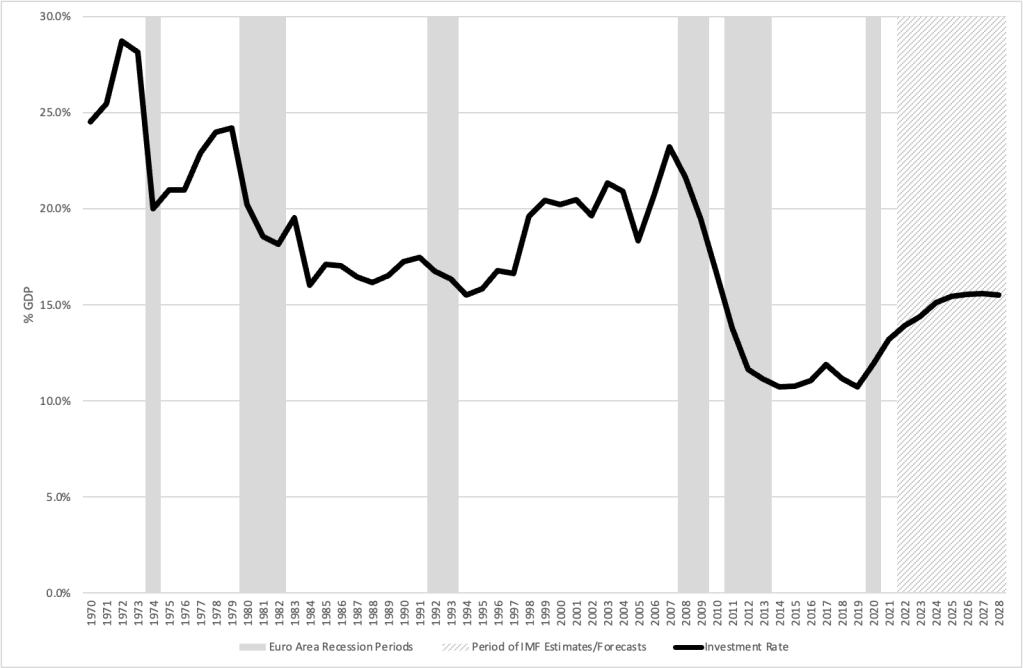

But even more important are the growth enhancing structural reforms that will lead to an increase in investment, productivity, and technical progress. Investment rates in Greece, especially after the 2010 crisis, are at hopelessly low levels (Chart 6). So is the rate of increase in aggregate productivity and technical progress. The government must make full use of the Pissarides report, which proposes several appropriate reforms which, if adopted, could lead to a new period of high growth. Corresponding reforms have been proposed in my 2021 book Before and After the Euro (Gutenberg Editions, 2021) and by other economists.

Moreover, with Greece unable to resort to currency devaluation due to its participation in the eurozone, the gradual improvement of international competitiveness requires increases in nominal wages that fall short of the sum of inflation and the growth rate of labor productivity. Given that in its medium-term forecasts for the period 2024-2028, the IMF foresees for Greece an average inflation of approximately 2.0%, and a growth rate of labor productivity (real GDP per employee) of approximately 1.5%, in order to have at least one and a small improvement in the international competitiveness of the Greek economy, the average increases in nominal wages should not exceed 3% per year for the entire next five- year period. Only if there is faster economic growth will there be scope for faster wage increases.

Finally, to reduce public debt as a percentage of GDP, it is necessary to maintain relatively high primary surpluses for several years and to engineer faster GDP growth rates. Given that during the pandemic public debt rose to above 200% of GDP, primary surpluses should be more than double the difference between interest rates and the economy’s growth rate for public debt to remain on a falling trend. In its medium-term projections for the five-year period 2024-2028, the IMF is based on rising primary surpluses, averaging 1.8% of GDP, starting with a primary surplus of 1.4% of GDP in 2024. These lead to a de-escalation of public debt as a percentage of GDP from around 180% of GDP in 2022 to 143% in 2027 (Chart 7).

The problem of achieving a significant acceleration of economic growth while simultaneously improving the international competitiveness of the economy is the main challenge of economic policy for the next four years. Higher economic growth relative to the current projections will also lead to a faster de-escalation of unemployment and the ratio of public debt to GDP. Bold reforms are needed, which a government with ‘free hands’, has no reason to delay in pushing forward with boldness and determination. The election result provides a historic opportunity for the government and the country.